(この投稿を日本語で読むのはこちらです)

It’s my belief that we should leave children’s learning up to their own curiosity, because learning that comes from curiosity is true learning that they will remember throughout their life, whereas learning that they have forced upon them is shallow and soon forgotten. As an example, I want to reflect on my school-based maths learning.

At 16 years old I got an “A” in my maths GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education, a national exam in England), an exam that involved extensive algebra and trigonometry. Getting an “A” means that at the time I really must have learned the material, and yet now I can hardly do algebra at all. I can’t solve any but the most rudimentary of problems. In 2005 I bumped into this rather hard when I was accepted into an elementary school teacher training course (a course I did not actually complete, but that’s a story for another day). As part of the course I needed to pass a maths exam, but upon attempting to review, I realised that I was having to learn algebra pretty much from scratch – by twenty-nine years old I’d forgotten nearly everything I’d learned at sixteen.

In addition (haha!), in relearning this math I learned something about algebra that I am quite sure I had never understood at sixteen (a friend explained it to twenty-nine-year-old-me, and it was quite a moment of revelation: “A-haaaa! THAT’S what that was all about!”).

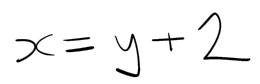

In algebra, you often need to rearrange an equation to figure out the variable you want, and one of the few things I did remember from my schooling was that when, in order to do this, you take a number from one side of the equals sign and put it on the other side, you need to also change its sign, from plus to minus or vice versa. For example, say you’ve got an equation

but you already know what X is and want to figure out what Y is. What you do is switch the +2 to the other side of the equals, and also switch its sign from plus to minus, so that the equation becomes

This much I remembered, but I had no understanding of why this works – at school this is what I’d been told to do, so I did it.

The actual reason is that you need to do the same thing to both sides of the equation – if you don’t then the meaning of the equation will change. So you aren’t really ‘moving’ the number and switching the sign: rather you are subtracting it from the right (subtracting 2 from “y+2” makes it just “y”) and also from the left (subtracting 2 from “x” becomes “x-2”).

This is a pretty fundamental principle of algebra, without an understanding of which you are going to have a hard job really understanding the rest. And yet although I am sure my maths teacher, Mr Hey, a nice guy who I remember well (but not his explanations…) made this clear, I am quite sure that I never understood this at all in school, probably because I wasn’t interested:

And without this key understanding, at sixteen I had fallen back on simply memorizing the methods I needed (something that was encouraged by the constant “practicing”, i.e. repetition of similar problems, that we did in class and for homework) with no real understanding of why they worked. To me this is not real learning: real learning involves understanding the principles underlying what you are doing.

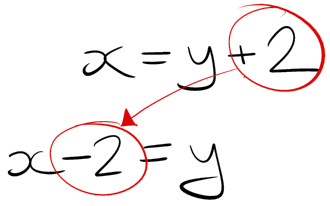

By contrast, at around ten years old I learned a programming language called BASIC (Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) and I can still remember it now, well enough to write this simple program from memory:

10 PRINT “What’s your name”

20 INPUT A

30 PRINT “Hello ”A

40 PRINT “How old are you?”

50 INPUT B

60 PRINT “Next birthday you’ll be “ B+1

70 IF B<20 PRINT “You’re still young!” THEN GOTO 100 ELSE GOTO 80

80 IF B<40 PRINT “You’re getting older!” THEN GOTO 100 ELSE GOTO 90

90 PRINT “You’ve got lots of experience!”

100 END

In case you don’t know BASIC (if you do, you’ve probably already spotted some errors – I’ll get to those in a minute), I’ll explain that this program has a short conversation with you: it asks your name and says hello to you, then asks your age, and based on your answer calculates your age at your next birthday and then gives a comment about that age. An example will make this a lot clearer:

Computer: What’s your name?

Me (typing): Simon

Computer: Hello Simon. How old are you?

Me: 41

Computer: Next birthday you’ll be 42. You’ve got lots of experience!

After I wrote this I decided I wanted to try it out, so I copy-and-pasted it across to http://www.quitebasic.com, a site that allows you to input and run BASIC programs. Initially, it was full of errors and wouldn’t run, but because I remembered the principles it only took me a short while with the help pages to get the program working smoothly (when you understand the underlying principles it’s relatively easy to reconstruct step-by-step methods that you may have forgotten, which is one of the reasons why learning that lacks this understanding cannot be considered true learning).

So, computer programming I learned at age ten I still remember at forty-one, but math I learned at sixteen (well enough to get an “A”) I’d forgotten by twenty-nine. What’s the difference?

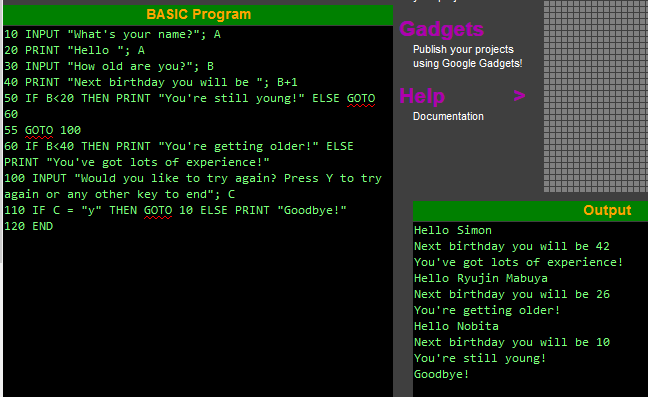

I think the difference is simply that BASIC was something I learned because I wanted to, purely out of my own curiosity. I learned it at home after school and on the weekends, getting the programming techniques from books, trying them out on our family computer (a Dragon 32: 32k of RAM, no hard disk whatsoever, and the internet wasn’t even a thing back then), and then using them to write my own programs which I would edit and tweak until they ran smoothly and to my satisfaction. Importantly, there was no one at all making me do this (my parents didn’t understand it at all) – I could have played soccer or read comics with this time, but I chose to spend it scratching my head over lines of computer code, simply for the fun of it. My imagination and creativity were working in overdrive as I puzzled out the way forward, and the result was real learning that I still remember 31 years later. (I experienced the same sense of fun tweaking my program above – I spent far longer on it than I really needed to for this blog post.)

By contrast, algebra was just something I was made to learn at school. I listened to and followed Mr Hey’s instructions, but I never had any idea why I was learning this stuff, which as far as I was concerned had no relevance at all to my own life, interests and enthusiasms. Although I performed the tasks well enough to get that ‘A’ my imagination and creativity weren’t engaged and so I never really made this material my own. And as such, nowadays I can’t remember it.

My point is that no matter what it is that we adults want children to learn, it’s the learning that a child chooses for herself that will stick – if she’s not interested enough in something to choose it for herself, then it’s simply learning that is being pushed upon her, and without the spark of curiosity this will never result in true, lasting learning.

So I think we should leave children’s learning up to them. Let them follow their curiosities, their instincts, their bliss. They’ll learn a lot of stuff that we adults might think is of questionable long-term value, but that’s not important (and who knows what use they may find for this learning in later life – an encyclopedic knowledge of Yo-Kai Watch may lead to a creative career in comics, games and animation). What’s important is that whatever it is that they get curious about and learn, at least it will be real learning, the kind they’ll carry with them for a lifetime. The alternative is learning that is never truly understood, and/or soon forgotten, and so might as well never have been learned in the first place.

“Real learning comes from curiosity” への3件の返信

コメントは受け付けていません。